Net Income versus Cash Flow

- Hurratul Maleka Taj

- 1 hour ago

- 4 min read

Net Income versus Cash Flow

In financial reporting, net income commands attention. It anchors headlines, drives valuation multiples, and often shapes investor sentiment. But profits, standing alone, are an incomplete measure of corporate health.

If earnings are the narrative, cash flows are the evidence.

Earnings quality, at its core, asks a simple question: Do reported profits convert into cash with high probability? When net income and cash flows move together, financial performance is likely durable. When they diverge materially, the quality of earnings deserves scrutiny.

The Structural Problem with Net Income

Net income is prepared under accrual accounting. Revenues may be recognized before cash is collected. Expenses may be recorded before payment or cash outflows may be capitalized and expensed in later periods. Non-cash items such as depreciation reduce profit without affecting liquidity.

As a result, profitability does not automatically imply solvency, resilience, or value creation.

A firm can report rising earnings while experiencing deteriorating liquidity. That is not theory. It is history. Many early 2000s accounting scandals were characterized by high earnings and weak operating cash flows - a classic warning sign of earnings management.

The solution is not to ignore profit. It is to contextualize it within the cash flow statement.

The Three Cash Flow Signals

A company’s statement of cash flows decomposes reality into three fundamental dimensions:

1. Cash Flow from Operations (CFO)

This is the most critical measure of earnings quality.

CFO reflects cash generated from core business activities - collections from customers, payments to suppliers, wages, taxes, and interest (under US GAAP).

Over time, if earnings are sustainable, they should broadly translate into operating cash. Persistent gaps, especially when net income materially exceeds CFO - signal aggressive revenue recognition, capitalized expenses, or working capital distortions.

Rule of thumb: Over a multi-year horizon, strong businesses convert accounting profit into operating cash with consistency.

2. Cash Flow from Investing (CFI)

CFI captures capital expenditures, asset purchases, and disposals.

Negative investing cash flow is not inherently bad. In fact, it often reflects growth. The critical question is whether operating cash can sustainably fund investment without excessive external financing.

Healthy firms invest strategically, not desperately.

3. Cash Flow from Financing (CFF)

CFF reflects debt issuance, repayments, equity transactions, and dividends.

For mature firms, repeated reliance on financing to fund operations can be a red flag. Financing cash inflows should complement - not substitute - operating cash generation.

When operations are weak but financing inflows are strong, the business model may be under stress.

The Ultimate Test: Free Cash Flow

Free Cash Flow (FCF) refines the analysis:

(A commonly used non-GAAP metric)

FCF = Cash Flow from Operations − Capital Expenditures

FCF measures the cash left after maintaining and expanding productive capacity. It is the cash available for dividends, debt reduction, share buybacks, or strategic flexibility.

Profits can be managed.

Free cash flow is generally harder to manipulate than net income.

Markets ultimately value a firm’s capacity to generate distributable cash, not accounting abstraction.

The divergence between net income and cash flow often arises through working capital mechanics. Revenue recognized but not yet collected increases accounts receivable and net income, while reducing operating cash flow relative to earnings. A buildup of inventory consumes cash without immediately affecting profit. Conversely, rising accounts payable can temporarily increase operating cash flow without improving net income. These timing differences explain why accrual profit and cash generation frequently move apart.

When the Market Enforces Discipline: The Meta Example

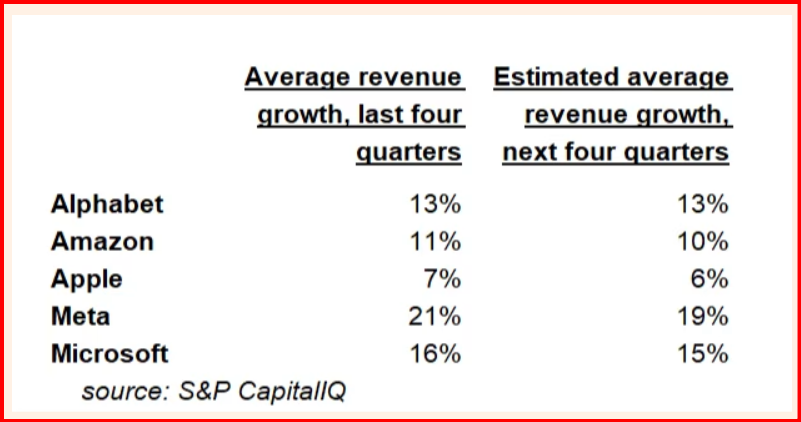

A recent Big Tech earnings season offers a textbook case.

In Financial Times, Oct 31, 2025 article: Big Tech earnings: profits and cash still matter, Meta reported strong revenue growth and solid earnings. Yet markets responded negatively. Why?

The issue was not sales. It was Cash Flow.

Meta significantly increased capital expenditures for AI infrastructure and data centers - at a pace exceeding its growth in free cash flow. In fact, among major peers, it was uniquely positioned to see free cash flow decline despite strong top-line performance.

Investors drew a line.

The narrative that “AI dominance justifies unlimited spending” proved incomplete. The market imposed guard rails: capital investment must be supported by credible cash generation.

In contrast, firms where earnings growth remained more closely aligned with free cash flow expansion were rewarded.

The signal was clear: revenue growth alone is insufficient. Earnings acceleration is insufficient. Cash discipline matters.

Earnings Quality as Strategic Insight

High-quality earnings exhibit three characteristics:

CFO tracks net income closely over time.

Investments are funded sustainably through operating cash.

Free cash flow supports long-term capital allocation without excessive leverage.

When these conditions hold, profit is meaningful.

When they do not, net income becomes an accounting construct detached from economic reality.

Final Perspective

Financial markets can appear captivated by growth narratives. Yet over time, they revert to fundamentals.

The companies that endure are not those that merely report profits—but those that convert profits into cash, reinvest prudently, and generate sustainable free cash flow.

In corporate finance, there is a hierarchy of truth:

Revenue tells a story.

Earnings refine it.

Cash flow confirms it.

And in the long run, confirmation is what counts.

Comments